Under The Hood: How Carb Back-Loading Works

By John Kiefer

Why is Carb Back-Loading so insanely effective? Well, before we get into the nuts and bolts of how everything happens on the cellular level, we first need to establish a bit of dietary philosophy in order to build a framework—and get some context—for this discussion.

Whatever type of diet we’re talking about here, whether we’re calling it Paleo, or primal, or green-faced, people originally created these programs to solve problems: cancer, inflammation, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, or even America’s claim to fame, the Metabolic Syndrome. In general, if you’re used to eating fast food on a regular basis, they’ll make you feel better. Once people feel better, they become more active—which can eventually lead to more rigorous training routines. When we reach this stage, we usually come to realize that the original diet can’t keep up with our goals.

That’s when we modify everything—throwing in change after change, trying to transform a stripped-down diet created to improve health into a fire-breathing performance enhancer. This, unfortunately, doesn’t work.

When it’s time to graduate to this level and enhance performance, I focus on the most powerful dietary tool there is: the carb. Sure, protein builds muscle, and fat forms the membrane of cells, but neither can manipulate the levels of as many different types of powerful hormones as dietary carbs. They can make us fat, help us sleep better, satiate us, and make us hungrier. Most importantly for our purposes, carbs can also unleash the potential for us to get huge[1,2].

Carbs trigger the release of insulin, which stimulates tissue growth—both in skeletal muscle and body fat. That’s why diets like my Carb Nite® were created—plans that limit carb intake for several days before adding a sudden burst of them. When you limit carbs, you burn fat, but your metabolism eventually wanes. Including them on some sort of schedule ramps your metabolism back into high gear to continue burning fat. Pretty much all physique coaches make use of carb manipulation in some manner.

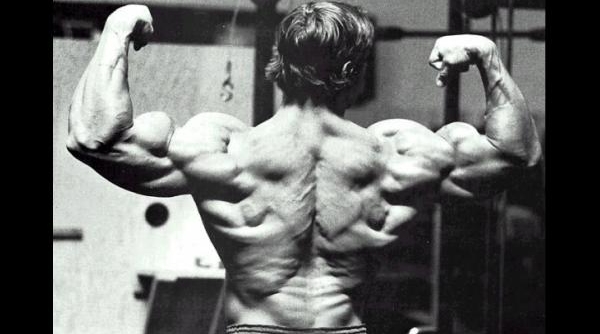

The idea behind all of these next-level plans is to get shredded while sparing as much muscle mass as possible. The problem, however, is that most diets contain bulking and cutting phases—with neither happening simultaneously. There’s still disputation out there, but it’s getting harder and harder to deny that insulin release allows muscle to grow. If nothing else, carbs definitely limit protein turnover—the destruction of muscle that normally occurs with resistance training[3]. If you want to be big and freaky, you need to eat carbs. But what if you want to be cut and jacked at the same time?

THE RISE OF CBL

For a long time, I listened to the handed-down wisdom that I should eat my carbs in the morning—and, trust me, I did. Plenty of them. Carbs in the morning meant added bulk and a solid training session later in the day, but it never meant staying lean—at least not easily. I eventually figured out that carbs were the problem. After developing Carb Nite and attempting to use it to build muscle and lose fat, I finally accepted that carbs are important for muscle growth. I gained some muscle as I leaned down—and got stronger and found my long-lost abs—but I hit a plateau. I was lean, strong, and going nowhere. Stagnation sucks.

That’s when I happened upon some interesting information while researching type II diabetes (non-insulin-dependent diabetes milletus, or NIDDM) and glucose clearance. Despite being heavily insulin-insensitive, diabetic patients could achieve temporary glucose control with resistance training[4]. Of course, diabetes doesn’t offer many advantages, but NIDDM actually develops as a way to prevent the body from getting fatter. Once NIDDM sets in, fat cells can no longer absorb sugar to store as fat. Resistance training, however, allows the muscles—which also become insulin resistant—to absorb glucose. The wheels in my head began to turn.

It seemed to me that there was a golden opportunity here to trigger muscle growth and empty fat cells at the same time. It’s a concept I call Modulated Tissue Response (MTR), which causes an anabolic response in one tissue, while simultaneously causing a catabolic response in another. In this case, it makes muscles grow and fat stores shrink. Carb Back-Loading represents one of the simplest forms of MTR possible.

WHY SO SENSITIVE?

Almost half of all males over the age of 25 have some degree of insulin resistance. Insulin sensitivity, one would think, is a good thing. If you want to stay skinny, however, it can work against you.

Insulin is linked to the subject of sugar—in this case, glucose—because insulin helps glucose enter cells for storage as glycogen or to be converted into fat. Insulin doesn’t do the actual work of getting the sugar into the cells, though. That’s accomplished by glucose transporters (GLUTs). We currently know of 14 of these: GLUT1 through GLUT12, HMIT (sometimes called GLUT13 for convenience), and GLUT14. Not all of these GLUT transport glucose molecules. Some transport fructose, while others actually hamper the transport of glucose. GLUTs 1 through 4 actually do transport glucose, however, and of these, GLUT4 is perhaps the most important for Carb Back-Loading.

Rather than shuttling sugar molecules through cell membranes, insulin recruits GLUT4s to do the work. When not active, GLUT4 proteins sit tucked within the membrane of the cell, doing nothing. Once insulin hits a cell containing them, the GLUT4s go to work by moving to the cell surface—a process called translocation—where they grab sugar molecules and move them into the interior of the cell[5]. The cell then uses the supplied sugar as energy or stores it for later.

Insulin sensitivity describes how reactive a cell is to the insulin-triggered translocation of GLUT4 proteins from the interior of the cell to the exterior where they do their work. If cells fail to react to insulin, GLUT4s move slowly and only partially to the cell surface. Total insulin insensitivity (or insulin resistance) happens when they don’t move at all.

Two tissues contain high amounts of GLUT4: striated muscle and fat cells. With high insulin sensitivity, both fat and muscle cells can soak up sugar to store as triaglycerol (fat) and glycogen, respectively. When you become insulin-resistant, neither can. You’re either fat and jacked, or skinny and weak.

We have, however, discovered something useful about the relationship between insulin sensitivity and the time of day. In the morning, cells with GLUT4 react more strongly to insulin than in the evening[6-8]. Think of this as a mini life-cycle that’s reset each night. All of us start our lives insulin-sensitive, but as we age, we become less so. The same things happen, just on a shorter time scale: we wake up insulin sensitive, and go to bed somewhat insulin resistant.

The circadian rhythm of insulin sensitivity—high in the morning, lower at night—is the main reason why most diet experts recommend eating carbs first thing in the morning, then tapering them off as the day wears on. If all you care about is growing—both fat and muscle, that is—I’d agree with this strategy. If you want to get leaner, though...

EXERCISE A LITTLE CONTROL

There’s another way to manipulate GLUT4 activation—one that doesn’t involve insulin or depend on the insulin sensitivity of cells. Best of all? We control this method.

Research about diabetic glucose control may seem like an odd place to find a useable procedure for healthy adults to get muscular and lean at the same time, but it’s not so odd when you understand glucose uptake as a function of GLUT4 activity instead of insulin secretion. When GLUT4 won’t translocate—like with type II diabetics—it doesn’t matter how much insulin the pancreas dumps into the bloodstream. The cells simply won’t absorb sugar well. Like I said, NIDDM is the body’s defense against getting too fat. Luckily, we have a variety of drugs that allow people to get as fat as their hearts, or stomachs, desire.

This is what struck me about a diabetic’s ability to lower blood sugar levels through resistance training. During resistance training, GLUT4 moves to the cell surface in muscle tissue regardless of insulin levels[9], a process called non-insulin-mediated translocation. If a person is insulin-resistant, training can help their skeletal muscle tissue use sugar, but their fat tissue still can’t. Resistance training gives us control over the molecular machinery within our cells, and it’s what makes MTR—and Carb Back-Loading—work.

If you'd like to see Kiefer's sources, click here.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

DH Kiefer is a Physicist turned nutrition and performance scientist. He’s been researching, testing and verifying what hard science proves as fact for over two decades and applied the results to record-holding power lifters, top ranking aesthetic athletes, MMA fighters and even fortune 500 CEOs. He’s the author of two dietary manuals, The Carb Nite® Solution and Carb Back-Loading™, and the free exercise manual Shockwave Protocol™. He’s currently considered one of the industry’s leading experts on human metabolism and plans to stay there. He’s a featured writer in every issue of FLEX and Power Magazine. You can learn more about him at www.dangerouslyhardcore.com.

Website: http://www.dangerouslyhardcore.com/

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/DangerouslyHardcore

Twitter: https://twitter.com/DHKiefer